Classic Car Catalogue

THE BUILDING OF ROLLS-ROYCE CARS.

The Swiss Alps.-The Rolls-Royce testing ground form an appropriate setting for the "Continental" Saloon.

The story opens with Mr. F. Henry Royce who was engaged in making high grade electric cranes in Manchester. Finding that the competition of lower priced goods from the Continent had undermined the market, he turned his attention to the making of motor-cars. From experience gained with various makes which he had owned and tried, he found out the various faults which beset them, and his first production, a two cylinder car which appeared in 1903, showed such an appreciation of the finer points of control, finish, and silence that it equalled the four cylinder machines of the day and drew unstinted praise from all who tried it.

The Hon. C. S. Rolls, whose name later became the first of the two in the famous "R.R." monogram, was at that time running a motor agency in London, and recognising at once the merit of the Royce cars, arranged to take the entire output. His racing and commercial experience supplemented the engineering knowledge of Mr. Royce and the cars appeared successfully in all sorts of competitions.

Royce cars were second in the 1905 T.T. race, and first in the race of 1906, and the business expanded so rapidly that in the following year the Rolls-Royce Company was founded, with plans for moving to Derby to an enlarged factory. The move was completed by 1908, the factory buildings, like every other matter appertaining to the cars, being designed by Mr. Royce. Their area at that time was about one acre, which has grown steadily year by year, increased of course also by the space required for manufacturing aero engines, till it now totals about 16 acres, and between five and six thousand workers are employed there.

Of the firms, two founders, only one remains. Charles Rolls was killed flying at Bournemouth in 1910, though not before the Rolls-Royce car had gained recognition as the world's supreme automobile production. Sir Henry Royce, who was knighted by the King in 1931 after the Schneider Trophy in recognition of his services to British Aviation, still remains Engineer in Chief, and apart from the new designs and improvements which he still originates, no new departure appears on a Rolls-Royce car or aero engine until it has passed the scrutiny of the engineering genius whose attention to the smallest detail has made the car supreme.

In order to retain complete control of the quality of the components, every part of the Rolls-Royce car, excepting a very few specialised accessories, is made at the Derby factory. The first department we visited was the aluminium foundry, where crankcases, gear-boxes, and various smaller components were being cast.

A centrally driven lathe machining car crankshaft.

We were unlucky in our visit to the iron foundry, as the actual casting is carried on only on alternate days. Instead we saw cores and patterns being made. The men engaged in making the former become so skilled that they can work almost without having to refer to drawings or patterns, their sense of touch becoming so highly developed. The making of moulds is an equally skilled job, and the expert can transfer the imprint of an incredibly complicated pattern to comparatively crumbling sand. Cylinder blocks are the most important components which emanate from the foundry and the Rolls-Royce engineers have evolved a special chilling treatment which makes the bores unusually tough. They are finished by honing and outlast the car without showing signs of wear.

The drop-forging shop is one of the most striking features of the Works. Coming in from the daylight, at first all one can see is the glow of the gas furnaces, where the steel is being heated preparatory to being forged, and the dim figures of men grouped round glowing pieces of metal on the anvils of the drop hammers. The hammer descends and the metal alters shape. It is taken to another anvil where it is hammered between dies of a different shape, then to a third where the surplus metal is trimmed off. Back again to the first, an application of gauges and a final blow and the finished part, now seen to be a valve rocker, joins the pile below the hammer. The operators develop an uncanny skill in controlling these ponderous tools, and as in the case the foundries, the parts, steering arms or whatever they may be require little more than cleaning up to bring them to the right side.

The two-ton steam hammer which was housed in the same buildings as the drop hammers was even more impressive, flattening a six-inch billet into a mushroom shaped forging ready for making into a propeller boss with a couple of blows which shook the building.

In a nearby bay we saw the first signs of anything which suggested car construction. Side members for the various chassis were arranged on the floor and were linked up by the front and rear cross members. Then each in turn was laid on a suitable platform, a cord was run from the centre point of the back cross-member to the front one, and the process of checking alignment began. Before the holes are drilled in the side-members, the dimensions of each is checked and those which are not perfect are rejected. Once again when the side members have been connected, the unhurried inspector with his trammels measures up the distance either side of the centre cord a score of times, and it is not until he has satisfied himself that every part of the frame is symmetrical about the centre line that it is allowed to return to the erectors for the fitting of the sturdy tubular cross-members which re-enforce the centre part of the frame.

A section of one of the Milling Departments, which is chiefly engaged on large casting machining.

The finished Rolls-Royce crankshaft is a beautiful piece of work, machined all over. It is first turned on a centrally driven lathe, and the webs are then ground all over by a more than human machine in which the grinding wheels swing backwards and forwards as the crankshaft revolves until the exact contour is reached. Cams are ground on camshafts in the same way, the rocking arm carrying the grinding wheel following the shape of a master cam at the rear of the machine.

The centre of the crankshafts are drilled, also the camshafts, using drills about four feet long. This centre passage is used as an oil channel, and also lightens the components.

The big-end journals of the crankshafts are also hollow, the three throws being drilled simultaneously. Channels are then drilled through the webs to carry the oil from one journal to another, and tapered aluminium caps close the outside of the holes through the journals.

Gear Cutting.

An immense amount of care is devoted to perfect gear-cutting, and the teeth of every gear-wheel are ground all over. The formation of bevels is a most interesting process, cuts being taken from either side of the tooth by two knife-shaped cutters, which work in an inch-wide jet of oil, and when they have finished the formation of one tooth, lift up and pass to the next. The gears are then heat-treated to normalise any stresses which may have arisen in machining, and are cooled in oil-baths under pressure to prevent them warping. Then like the straight tooth type they are taken to the grinding department, where thin specially shaped stones bear on all the working surfaces. The grinding wheels are re-faced after each gear has been treated, in order to make sure that they shall not vary, and in the case of the timing wheels, the teeth are finished off by hand to ensure complete silence of operation.

Checking for accuracy.

Although the material from which the various engine and other parts are made is very carefully selected, and samples from every batch undergo tests in the laboratory, slight flaws are bound to occur, and in the machine shop as in every part of the factory, a considerable part of the department is devoted solely to examination of each article which is used. Each component is checked with delicate gauges and micrometers and every part of it examined under a magnifying glass. Even this scrutiny cannot always detect hair-cracks almost invisible to the human eye, so additional tests are undertaken.

In the case of material such as iron or steel, which can be magnetised, the part to be examined is placed within the field of a powerful electric magnet. It is then dipped into a bath of paraffin containing very finely divided iron filings and taken out and allowed to dry slightly. If there are any flaws in the metal, the iron filings collect along the line of the defect and reveal the otherwise undetectable weak spot.

This method of testing is of course not applicable to parts made of non-magnetic metals, such as brass or aluminium. In this case the object to be tested is placed in a bath of warm oil, and then as much as possible is wiped off. French chalk is dusted over the surface, and in a short time any crack which may exist is revealed by an oil speck in the chalk dust.

The Cloudburst process is used for checking over the hardness of such components as valve rockers and it also increases the hardness produced by heat-treatment. The rockers are clamped with their hardened surfaces upwards under a vertical shaft, and steel shot is allowed to fall continuously from predetermined heights. The slight hammering effect caused by the falling shot closes up the pores of the metal and increases the hardness. On the other hand if the heat treatment has been unsuccessful, the falling shot produce a mottling effect which is easily detected by the practised eye.

One of the Car engine Test houses. Engines are run here for a number of hours at varying speed

and loads prior to fitting into the chassis.

and loads prior to fitting into the chassis.

In another part of the shop, car steering-gears are being "run in." The worm is first of all polished with French chalk and then its shaft is fixed vertically in a machine which rotates it alternately first in one direction, then the other. The nut which is the other steering member is threaded on, and then weights totalling nearly half-a-ton are fixed to it. With chalk and oil as a lubricant the worm is rotated backwards and forwards, raising and lowering the weights each time. After a period of such treatment any stiff spots are eased, giving light and perfect steering throughout the life of the car.

After the engines have been erected, they are given a five-hour run. A continuous supply of oil is forced through the bearings, flushing out any foreign matter, and is cleaned and filtered before being used again. Coal gas is used as the fuel, to avoid any chance of washing the oil from the cylinder walls. After this flushing process the engine is taken down and the parts washed and examined. Coming satisfactorily through this inspection, the unit is re-assembled and brought to the engine test house, where it is given seven hours' running. Horse power readings are taken at various speeds. The "25" gives 85 h.p. at 3,500 r.p.m. and the Continental about 135 at 2,500, which goes far towards explaining its phenomenal pick-up on top gear.

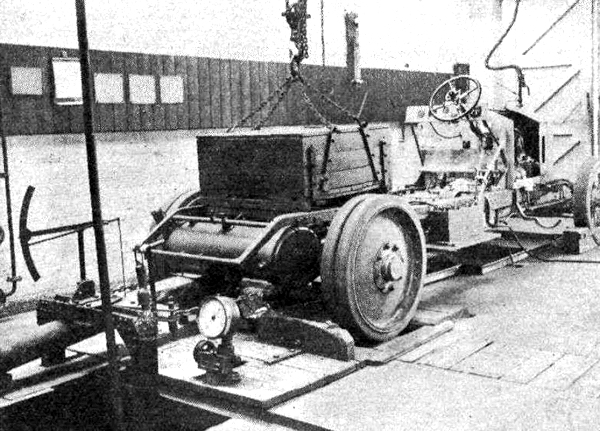

The gear-boxes are built up with the same care as the engine, particular attention being paid to silent running. They are then fitted to the engines, and the unit is erected into the chassis, ready for the chassis dynamometer test. In this the chassis is fitted with solid tyres at the rear, which bear on steel drums. The shaft on which the drums rotate can be braked to varying extents by adding or removing weights to balance the pull exerted. The chassis is fixed in position with chains and blocks, and the engine is then started. It is tried in turn on all gears, and the readings attained show up any tightness or other defect in the transmission. As in every other department of the Rolls-Royce works, the most extreme precautions are taken against errors of any kind, and the barometric reading, the diameter of the driving tyres, and the variation of tension of the brake band are all allowed for.

A 40/50 h.p. chassis being tested on the Prony dynamometer.

The Aero-engines.

Any article on the Rolls-Royce Works would be incomplete without a mention of the aero-engines produced there. The standard of workmanship used in manufacturing the cars is so high that no special precautions need be used in making the aircraft units, and the same tools and the same operatives work indifferently on one or the other. The engines are tested in a great row of test-houses, and even when their exhaust gases are led away through enormous water cooled silencers it is almost impossible to hear oneself speak and the testers wear cotton wool in their ears. Nearby are special open air test beds which can be tilted or inclined to give the conditions under which the engine works in the air, and tremendously strong wire torpedo netting protects workmen from the possibility of a broken propeller.

Radiators and Tanks.

In an article of this length it is impossible to do justice to the various subsidiary activities which play a part in the perfection of the cars, but one must mention the tank shop, in which sheets of tinned steel are double-rivetted and sweated to form the immensely strong petrol tanks and other articles of this sort. The famous Rolls-Royce radiators are also made at Derby, dozens of copper tubes being fitted in a frame and dipped in molten solder to a depth of inch, the same treatment being then given to the other end. The tubes are hexagonal at the ends and circular in the centre and have a series of projections inside. These projections break up the air stream and greatly improve the efficiency of the radiator.

Every department of the Derby Works reveals its own example of the care and skill which go to the production of the finished car, and the elimination of any possible sources of trouble or wear. The silence, long life, and perfection of performance and control of the Rolls-Royce are the inevitable result of this craftsmanship and attention to detail.

Park Ward's special touring saloon, a 1933 20/25 h.p. GBA39. The luggage boot is well integrated into the body line, and the reverse curvature at the door bottoms makes it less slab-sided.

THE TRAITS OF THE LARGER CHASSIS, ACKNOWLEDGED TO BE THE BEST IN THE WORLD, EMBODIED IN A DIGNIFIED, YET BRISK MOTOR-CAR

Refinement ant the highest grade of workmanship are conveyed in the frontal

view of the 20/25 h.p. Rolls-Royce.

view of the 20/25 h.p. Rolls-Royce.

The six-cylinder engine is mounted in unit with the four-speed gear-box, and the unit is suspended from four points. Two arms, one from each side of the front end of the crankcase, join in front of the engine and rest on a pivot on a cross member. Two more arms at the rear end of the engine take the weight of this part and a fourth support on the gear-box complete the suspension. Special dampers on either side of the engine limit the movement, and all these precautions make the power unit as smooth at high speed as at low.

A monobloc casting is used for the cylinders, and the detachable head carries push-rod operated overhead valves. Two valves per cylinder are used, and a single sparking plug is placed on the off side. Coil ignition manufactured by Rolls-Royce Ltd. is used for normal running, but in the unlikely event of its failure a Watford magneto can be brought into operation by moving a hand-adjusted coupling into engagement with a dog on the end of the dynamo. The lead from coil to distributor is detached and replaced by one from the magneto, and the car is ready to proceed.

A large Autovac tank on the dash supplies fuel to the Rolls-Royce carburettor, a precision instrument which can be dismantled practically without the use of tools. It is fitted with an economy control operated by a lever on the steering column, and an auxiliary starting carburettor supplies a rich mixture which ensures an instant start even after the car has been idle for several weeks.

The carburettor is mounted on the offside of the block and the mixture is warmed by its passage to the induction pipe on the near side. A centrally disposed exhaust pipe keeps heat and fumes well away from the driving compartment.

Alloy pistons which are as silent when the engine is cold as when it has warmed up, and a seven-bearing crank-shaft, complete the specification of the magnificent power-unit. The detail work, such as the lay-out of the control rods and the large number of securing bolts or studs used for securing any parts which are subject to strain help to maintain the Rolls-Royce reputation for longevity and freedom from trouble.

The off-side of the engine with the carburettor and distributor.

On the near side of the gear-box is mounted the mechanical servo-braking system. A cross-shaft driven by worm gears carries a disc; when the foot-brake is depressed, a clutch is forced into contact with the revolving disc, and the ensuing pull is used to apply the front and rear brakes. In addition, the brake pedal has a direct connection to the rear brake operating shaft, so that the pair on the rear wheels receive twice as much pressure as those on the front. With this arrangement, should the servo-mechanism fail, the pedal is still coupled directly to the rear brakes. A swinging lever balances the pull transmitted to the front and rear sets, and special compensators, which embody a bevel and pinion mechanism similar to that of a differential, equalise the effort between the individual brakes. The hand-brake operates separate shoes in the rear brake drums.

An open propeller shaft with two special metal universal joints drives the back axle, through spiral bevel gears. The back-axle is of the fully-floating type in which the weight of the car is carried by the casing, and the closely spaced bolts round the bevel casing ensure long life and a freedom from oil leakage.

The chassis is of orthodox type, dropped in the centre to lower the centre of gravity, and extremely rigid. The road-springs are of exceptional length and pass underneath the axles. Hydraulic shock-absorbers are fitted. The brake drums are of large size, and the brakes are cable operated.

We took over the "25" in a fairly busy part of London, and from the moment we occupied the driving seat we were impressed with the car's smoothness and ease of handling. Second gear is used for for starting, and the clutch is finger light and absolutely smooth. The brakes were powerful and came on steadily with increasing pressure of the pedal. Third and top gears, the ones generally used, were inaudible, and changing was rendered quite fool-proof by the synchro-mesh mechanism. The change to second gear, which ran with a well-bred and faint hum, was as easy as could be contrived with sliding pinions.

The steering wheel came right into the lap, and a correct driving position was easily found with the readily adjustable front seats. The hand-brake and gear levers were within comfortable reach, and the fact that the near side wing is clearly seen is a great help in traffic.

Brief Specification.

Engine:

6-cylinder 3¼ in. and 4½ in. bore and stroke

(81.6 mm.. and 114.3 mm.).

Capacity 3,699 c.c.

R.A.C. Rating 25.3 h.p.

O.H.V. push rods.

Single Rolls-Royce carburettor.

Coil ignition with emergency magneto.

Gearbox:

4 speeds and reverse.

Silent third.

Easy change mechanism for third and top gears.

Ratios 4.55, 6.25, 9.41, and 15.04 to 1.

Rear Axle:

Spiral bevel.

Full floating.

Suspension:

Half elliptic,

hydraulic shock absorbers.

Dimensions:

Wheel base 11ft.

Track 4.t. 8in.

Price:

Chassis £1,050.

Hooper Sports Saloon as tested £1,625.

Engine:

6-cylinder 3¼ in. and 4½ in. bore and stroke

(81.6 mm.. and 114.3 mm.).

Capacity 3,699 c.c.

R.A.C. Rating 25.3 h.p.

O.H.V. push rods.

Single Rolls-Royce carburettor.

Coil ignition with emergency magneto.

Gearbox:

4 speeds and reverse.

Silent third.

Easy change mechanism for third and top gears.

Ratios 4.55, 6.25, 9.41, and 15.04 to 1.

Rear Axle:

Spiral bevel.

Full floating.

Suspension:

Half elliptic,

hydraulic shock absorbers.

Dimensions:

Wheel base 11ft.

Track 4.t. 8in.

Price:

Chassis £1,050.

Hooper Sports Saloon as tested £1,625.

Experience on the open road confirmed this idea. On an undulating main road the car would maintain a speed of over 70 m.p.h. indefinitely, and slopes of 1 in 15 or so did not seem to slow the car at all. This untiring travel on top gear was equally noticeable at a slower gait, the high torque at low engine speeds making it unnecessary to rush hills in order to avoid changing. The maximum speed on the level was found to be 76 m.p.h., while on favourable gradients 80 was attainable without fuss. On winding side-roads the gears were used to some extent, 45 and 55 being reached comfortably in second and third.

These figures, satisfactory as they are for a touring chassis carrying a luxurious saloon body, only express a small part of the charm of the 25 Rolls-Royce. An equally important feature of the car is the way in which it responds to the controls and the untiring way in which its passengers are conveyed on their journey.

Take, for instance, the steering. Light enough to be handled effortlessly by the so-called weaker sex, it yet combines the high gearing and self-centring action which one expects on the race-bred sports car. An upright driving position with excellent visibility help to make prolonged driving effortless, and the controls come to hand with the minimum of movement. The lightness and delicacy of action of the clutch and brakes have already been remarked on. From 40 m.p.h. the brakes brought the car to rest in 58 feet, in spite of the locking of one of the back wheels. This trouble was probably due to oil in one of the drums, which would normally have been attended to when the car came in for overhaul after its Continental trip.

With his left foot the driver can reach the one-shot lubrication pedal, which is carried to all but four chassis points, none of which requires frequent attention. Closer are the starter pedal and the dipping switch for the headlights. This latter arrangement is very convenient, the only disadvantage being that one is liable to depress the starter switch when wishing to dip the lights. On the latest cars the starter is controlled from the dash.

The suspension is such that throughout the speed range the passengers are unconscious of the nature of the road surface. This suppleness is achieved without a trace of the objectionable rolling which is often the companion of flexible springing, and the car can be taken round fast bends in the most satisfying way. The comfort of the back seats was as great as that of the front ones, as they are well within the wheel-base, and we were able to make quite legible notes as the car was running at 60 m.p.h. along a road of inferior surface.

The 20/25 h.p. Rolls-Royce Sports Saloon by Hooper.

Turning from the body to the accessories, one of the most important items are the lamps. Part of our journey was accomplished in darkness, and the Lucas Biflex type fitted proved adequate for fast touring speeds. The dipping reflectors, operated by the foot switch already mentioned, enabled a fair speed to be maintained even when meeting oncoming traffic. Lucas P 80 or P 100 lamps are fitted as alternatives, and for really fast driving on the Continent their more powerful light would be agreeable. The windscreen wiper was a new pattern Lucas, in which the motor is carried at the near side of the screen, well above the line of vision of the passenger, and drives two large blades by means of a neatly enclosed shaft.

In this road-test we have considered the "25" Rolls-Royce simply from the point of view of a sports car, an attitude amply justified by its acceleration, and all-out speed coupled with its road-holding qualities and the liveliness of its response to the steering and controls. In actual fact these sporting qualities are present not as an end in themselves, but as a result of the essential soundness of the car as a whole. It is built simply as a refined vehicle of the utmost smoothness and flexibility, and it is equally happy at high speeds and when moving at a walking pace on top gear. All its work is performed with uncanny silence and absence of effort, qualities which make it the ideal town car. Such smoothness, allied to the magnificent workmanship which has always been the keynote of Rolls-Royce construction, must have a great bearing on the length of life enjoyed by the products of the Derby works.

Fortunate, then, is the owner of a 25 h.p. Rolls-Royce, for he has at his behest two or three cars in one. Crawling slowly through London traffic to Lord's or Roehampton, cruising at 40 m.p.h. through the pleasant countryside of England, or all out along N 7 en route for Juan or Cannes, the occupants enjoy the same silent travel. The handsome radiator, modernised in line but still symbolic of the aims which lie behind the initials "R.R," and the dignified and graceful coachwork which of late years our English builders have learnt to produce, together combine to form the Best Car in the World.

In perfect proportion are the lines of this Touring Saloon by Park Ward on a 20/25 h.p. Rolls-Royce chassis.

The car is finished in pastel blue with a dark blue belt rail and silver roof and upper parts. The interior is upholstered in pastel blue leather. The colour scheme imparts to the car an unusual lightness of appearance in keeping with the lively performance of the chassis.

There are two sliding bucket seats in the front and the rear seat carries two or three persons. A large trunk at the rear is built integral with the coachwork and contains three suitcases. A picnic table and stools are also stored there. A luggage grid is provided and folds away when not required behind a hinged flap at the bottom of the trunk.

A sliding sunshine roof is fitted, stainless steel wheel discs, two spare wheels with special covers, and the four-wheel jacks are operated by a detachable handle which is kept under the bonnet, together with the road tools. Spare petrol and oil is carried in a box in the chassis frame and reached through a hinged door in the running boards, likewise a fire extinguisher.

The easily operated head of this 4-seater coupé by James Young of Bromley, makes this 20/25 h.p.

Rolls-Royce particularly suitable for the owner-driver.

Rolls-Royce particularly suitable for the owner-driver.

Folding tables are fitted to the back of the front seats. When opened they reveal writing sets and companions. A car heater which derives its heat from the water supply can be controlled by hand.

The James Young Drop Head Coupé, also fitted on a 25 h.p. chassis, should be an ideal car for the owner-driver. It is carried out on quiet, graceful lines, and provides comfortable accommodation for five persons, with a large luggage locker formed in the back of the body. The folding head is exceptionally easy to operate, and is designed so that it can be thrown back without having to get out of the car to fold away any of the hood material.

Luxurious travel is the keynote of this sedanca body by Gurney Nutting on a 40/50 h.p. Continental Rolls-Royce chassis.

The front of the car is striking in appearance with its large P.100 lamps, and an unusual radiator stone guard of diamond-section plated strips. The Chromos bumpers have moulded rubber ends saving the bumper bar from breakage.

A luggage trunk is fitted with suitcases, also a compartment for golf clubs and a spare supply of petrol and oil, and tools are stored in the lid, and a lamp inside it lights up the interior of the trunk.

Two windscreen wipers driven by concealed motors are used, and a Grebel spotlight is carried on the off-side. Map-reading lamps are fitted under the scuttle, and the indirect lighting of the instruments is controlled by a Eural horn ring on the steering-wheel, while a larger one is used for the horn. A Philco wireless set is carried in the forward compartment, and its controls are finished uniformly with the other instruments.

A folding arm-rest invisible when not in use, makes the rear seat suitable for 2 or 3 passengers. Tables with mirrors are fitted to the back of the front seats and cocktail sets are found in the rear quarters. The rear window can be lowered by means of a handle concealed in the arm-rest recess.

A Hooper sports saloon on a 1933 Phantom II Continental 30PY, two-toned in grey and dark maroon. This car was built for Hooper's Managing Director, and had a number of experimental features in the body, such as alloy door pillars. One can see how the Evernden design is being gradually made more rounded as time goes on.

Rallies:

| Event: | Entered: | Raced: | Finished: | Best results: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

2 | 2 | 2 |

|

Jaques / Allan | 30th | ||

|

|

S. Harris | ? | ||||||

Winner of Class 4 in Coachwork Competition at R.A.C. Rally, S. Harris' beautiful James Young Continental Saloon.